Education

8:00 am

Mon January 7, 2013

Muskegon Heights school leaders “building the airplane as we fly it”

This story is the fourth in a four-part series about how things are going so far in Michigan's first fully privatized public school district. Find part one here, part two here, and part three here.Students in Muskegon Heights are going through a lot of changes this year, because the entire school district was converted to a charter school system. After tackling some tough issues in the first half of the school year, the operators of the charter school system want the public to give them a full school year to put the changes in place.

Former lawmaker: school system's fate lies in state policies

Muskegon Heights Public Schools faced such a huge budget deficit last spring, the state appointed emergency manager laid off the staff, teachers and all, and hired a charter school company to run the new school district he created.

He says the financial situation was so bad he didn’t have a choice.

But former Democratic State Representative Mary Valentine doesn’t buy that.

“There’s no other alternatives because that’s the way our legislature has worked it,” Valentine said.

Mary Valentine has become a vocal critic of the new charter school district in Muskegon Heights. She thinks state policies around schools of choice, charter schools, and school funding are impacting public school districts in negative ways.

Valentine’s been very interested and very unhappy with the changes at Muskegon Heights schools under the emergency manager.

“Anytime you put someone in charge of a school district who will fire all of the teachers and pull that safety net out, it is very clear they don’t know what they’re doing and how they’re hurting children. So why are we putting people like that in charge of our schools?” Valentine asked.

Valentine was a speech therapist in public schools for 30 years. At her home office in Norton Shores, which borders Muskegon Heights, Valentine proudly displays a signed picture of herself and President Barack Obama.

She fears that Republican state lawmakers are looking for cheap solutions to the complicated problems facing cash-strapped school districts and she’s speaking up about it. She wants to see lawmakers put forward “solid, research-backed solutions”.

“If they cost a lot of money then we should pay for them anyway, because it’s a lot cheaper to pay for good schools than it is to pay for prisons and there isn’t any way around it,” Valentine said, “Let’s bite the bullet and do what we need to do to make it a good solid school system.”

Muskegon Heights students, families keep watch on "work in progress"

A couple hundred parents and students spread out in the Muskegon Height High School auditorium for the December school board meeting.

The hot topic on the agenda was mid-year implementation of school uniforms at the high school.

A letter informing parents of the policy change went home less than two weeks before Christmas. Many parents felt that did not leave them with enough time to fit the cost of new uniforms into their budgets before January 2nd. Eventually, the board opted to delay uniforms at the high school until next school year.

“As a student I can honestly say there are bigger and better things to worry about at school right now than uniforms,” 17-year old Trevon Kitchen, a high school senior, told the charter school board.

Kitchen and other students started listing things off for the board. They don’t feel like they have any help researching or applying to colleges. Young, new, teachers can’t keep kids in class under control. Many are unhappy with their class schedules.

Kitchen wants to be a computer engineer. He says he certainly didn’t pick a class about music appreciation.

“Can I tell you what I learned in that class? No, because I didn’t learn anything. I can’t even take a pre-calculus class that I need for college,” Kitchen said.

“If we would’ve been paying attention the first time around we wouldn’t be in this situation now. So we’re trying to get better at it,” Trevon Kitchen’s dad, Roger Kitchen said, speaking in part to the parents in the room.

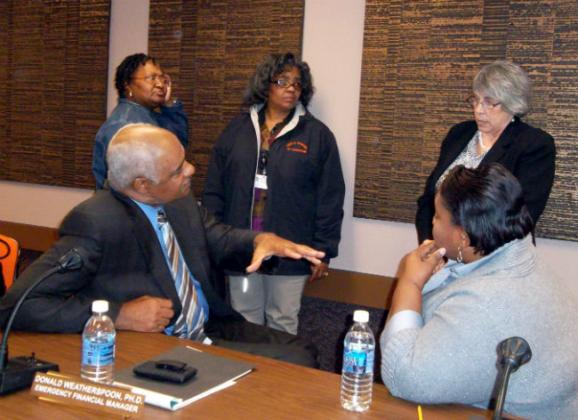

Roger Kitchen, the parent of a Muskegon Heights high school student, makes a heartfelt plea with parents near the end of a tense charter school board meeting December 17th.

“We’re not blaming ya’ll or pointing fingers. You’ve got your hand full,” Roger Kitchen added, pointing at the school board and administrators on stage.

He looks around at frustrated parents as he speaks. “We have to get out of this together. We can’t point fingers because it starts with us. So we got to do better – we got to be held accountable too…We can’t blame them. This starts at home,” Kitchen said.

New system needs time: "We're building the airplane as we fly it."

School administrators say they understand things aren’t perfect.

“People should definitely hold us accountable,” Mosaica Education Regional VP Alena Zachery-Ross said. But she cautions that the company, staff, and students need more time to adjust. “I want people to realize that it’s going to take the full year,” Zachery-Ross said.

"It takes time to build a foundation," Zachery-Ross said, "Any house that’s built too quickly and doesn’t have a strong foundation, in the long run it falls down and it’s not secure. We are building the foundation."

“Well remember, I said we were building an airplane as we fly it,” Muskegon Height schools’ Emergency Manager Don Weatherspoon said, “Nothing is going to be perfect in its first year.”

Weatherspoon says it’s “very easy for people to develop negative impressions” about the district and says that’s wrong. He says it’s unfair to judge the new system too soon.

He’s expected to hire an outside consultant to independently evaluate the charter companies running Muskegon Heights and Highland Park schools. He’s now managing both school districts.Don Weatherspoon says the community has regrouped around the new school district, and it's wrong to develop negative impressions.

He points out Mosaica is working with community groups to re-open the high school pool. The company is working on a teacher retention program, and he says student enrollment is higher than he expected.

Last year there were 1,265 students at MHPS. This year there were 1,112 on student count day in October. But Mosaica’s records show attendance had increased to 1,211 by late November. Mosaica had more than 1,400 students in their budget plan that was adopted by the charter school board in July.

Weatherspoon estimates it’ll take the old school district up to 20 years to pay off all its debt. He points to the community's support for a property tax renewal in November as proof they've "regrouped" around the new school system.

“If you look at where this community has been and what it’s done for itself you’ve got to say ‘wow’, because at the beginning of this year there was total despair," Weatherspoon said. "Now, did some things happen that were disruptive? Absolutely, and there were some hard decisions that had to be made."

Could this happen to other cash-strapped Michigan school districts?

Weatherspoon was appointed to run the district in April 2012 under Public Act 4, commonly known as the emergency manager law. That law allowed managers to break union contracts, in this case laying off the school staff, and forming the new charter school district, which then hired Mosaica Education.

He got all that done before Public Act 4 was put on hold and eventually repealed by voters in November. At that point, a former version of the emergency manager law took effect, a version that would not authorize an emergency manager to break union contracts.

“Yes, we were very fortunate that we got (the charter contract) done when we did,” Muskegon Heights Public Schools attorney Gary Britton said in November 2012, shortly after Public Act 4 was repealed.

Governor Rick Snyder just signed a new emergency manager law. It goes into effect later this spring.

Under the new law, the privatization of a school district could happen. Emergency managers will once again have the power to break part or all of union contracts; although there are more stipulations in the new law.

Governor Snyder on privatizing public schools: “The kids don’t care”

I got a chance to sit down with Governor Snyder shortly before the November election. He was taking a tour bus across the state to urge voters not to repeal the emergency manager law he signed. Don Weatherspoon was along for the ride.

“Bankruptcy is not a trivial act. It’s a major issue,” Snyder said. The basis for the law was that one city or school district’s bankruptcy will hurt the credit rating of not only that district, but the credit rating of surrounding communities and the state's too. So the law gave emergency managers broad powers to avoid bankruptcy.

I asked what Snyder thought of a private, for-profit company running a whole public school district, like in Muskegon Heights school (and Highland Park schools).

In late October, Governor Rick Snyder says the concern shouldn't be about who runs schools, but whether students are getting a great education.

“The real question isn’t ‘are they not for profit or for profit?’ It’s ‘are the kids getting a great education?” Snyder answered.

“The kids don’t care,” Snyder continued, “I’ve never had a child come up and say, you know, I need to have a for-profit or a not-for-profit. They want to get a great education, so that’s the driving consideration in this whole discussion.”

The new emergency manager law (Public Act 436) does require managers to submit an “education plan” to the state. But the conditions under which the “emergency” is triggered or resolved are financial, not academic in nature.

The new law provides more options for financially troubled school districts and municipalities up front (options besides the appointment of an emergency manager), and a more clear transition process once the finances are in order.

David Arsen is a Professor in the Department of Educational Administration at Michigan State University’s College of Education. He co-authored a study on Public Act 4 shortly before it was repealed in November that concluded the law “does not address student learning and could even hurt academic performance in high-need communities.”

Arsen says it would be “hard for the very best administrators in the state to avoid deficits” given the situations in such districts. He says state education policies, particularly funding policies, can play a big role in those districts getting into deficits in the first place.

“As much as we’d like to think so, these are problems that can’t be solved simply by changing the boss. It’s wishful thinking,” Arsen said.

Arsen says Public Act 4 didn’t have “basic provisions” for academic accountability. He noted that emergency managers were required to have expertise in business and finance, but the law says nothing about required experience in education if a manager is appointed to a school district.

A read-through of both the now repealed Public Act 4 and the new Public Act 436 shows identical requirements for those individuals considered to be emergency managers.

(a) The emergency manager shall have a minimum of 5 years’ experience and demonstrable expertise in business, financial, or local or state budgetary matters.Arsen declined to comment on the new emergency manager law, since he has not had adequate time to study it yet.

(b) The emergency manager may, but need not, be a resident of the local government.

(c) The emergency manager shall be an individual.

Public Act 436 goes into effect March 27th, 2012.